Researching the Integration History of Your Library

Has your public library always been open to all residents?

Are you sure? Many libraries, especially those in the Southern United States, have a buried history of racial segregation that isn’t found in books or websites and is often unknown to current staff and community members. Through archival research and oral histories, you can help uncover clues about your library’s past.

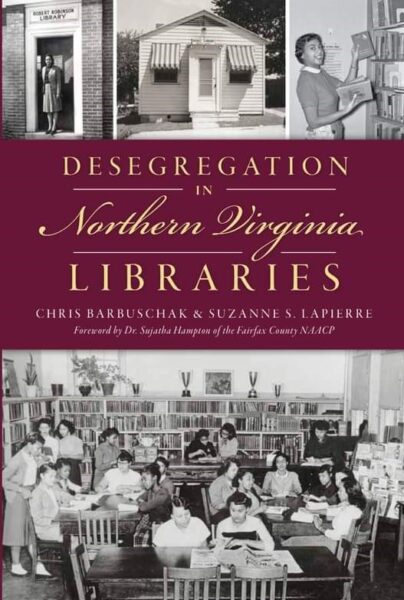

In April of 2021, the Fairfax County Public Library board of trustees requested an investigation into whether our library system- and those around it- had ever been segregated. The question was referred to librarians at the Virginia Room, our library’s center for history and genealogy research. When we began studying the segregation history of libraries in Northern Virginia, the case of Samuel Tucker in Alexandria was the only one that was well known. Tucker was an attorney who masterminded a 1939 sit-in to protest the library’s whites-only policy. We had no specific knowledge of other public library systems in the vicinity having been segregated. But as we dug deeper, we discovered a hidden history of exclusion, segregation, and unequal treatment in many of our local public libraries.

It’s important to know about our past and honor those who helped achieve more equity in libraries. Getting started can be the hardest part. Based on our experience, these are some places you can begin to investigate your own library’s history.

Where to Look

-

- Surviving in-house records in your library’s archives or files. These might include library board minutes, circulation statistics, newsletters, manuscripts, and other ephemera, especially that from the Jim Crow era. For example, our archives included monthly record forms from the 1940s divided into statistics of Black and white customers. The sections for Black customers had been crossed out by many librarians–indicating their branches did not serve Black customers. Library board meeting minutes from that time revealed the scarcity of bookmobile stations for Black residents and the decision to keep separate bookmobile materials for Black and white customers.

- Surviving records at your state library, including state library reports and minutes. The situation at the state library might not align with that at the town or county level. For example, while the Library of Virginia complied with the Virginia state mandate that public libraries receiving state aid must serve all residents (which was the law at least as early as 1946), many local libraries in Virginia nevertheless continued to exclude Black residents while accepting taxpayer funding, even into the 1960s.

- Newspaper articles, including both Black and white newspapers published during the Jim Crow years. In addition to coverage of library protests and lawsuits, you’ll find very different attitudes towards events expressed in editorials, depending on the publication’s intended audience or slant. Opinion pieces are indicative of how many residents may have reacted to integration at that time and place.

- Previously published books, especially those focused on your region. A good overview can be found in the book “The Desegregation of Public Libraries in the Jim Crow South: Civil Rights and Local Activism,” by Shirley A. and Wayne A. Wiegand, LSU Press. Microhistories include “Public in Name Only: The 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In Demonstration,” by Brenda Mitchell-Powell, University of Massachusetts Press.

- Thesis work. Bernice Lloyd Bell’s 1962 thesis “Integration in Public Library Service in Thirteen Southern States, 1954-1962” is a good starting point for researchers. She surveyed 290 Southern libraries to determine their level of services to Black residents and provides dates for when those libraries were desegregated.Memoirs of people who lived during that time. In his memoir “Life After Life,” Danville native Evans Hopkins shares his experience as a child using the tiny two-room library reserved for Black residents of Danville, Virginia. He also writes about the shock he felt when he was finally allowed to use the main public library after it was integrated- only to find that all the tables and chairs had been removed to keep Black and white customers from sitting together.

- Oral histories. Speaking with older members of the community, relatives and co- workers of key players, and colleagues at other institutions can fill in many blanks in the story and add personal insight. Sources include Friends of the Library groups, African American history and genealogy groups, local history clubs, and current and retired library staff.Your colleagues at other institutions can be very helpful. They may already know a lot about their organization’s history, or at least be able to point you to the best sources. They may know people who would be good candidates for oral history guidance. There’s no point in reinventing the wheel, so be sure to find out about research they’ve already done or have in progress.

- Local archives. Make appointments (if necessary) to view manuscript collections at other local libraries, museums, and archives. Do fliers about library grand openings or old library card applications state that the library is open to all residents? Do photographs from events show integrated groups in attendance?

- Current landmarks. Do some foot work by visiting existing sites and landmarks that you know of already or uncover in your research. Sometimes just showing up and exploring sites in person can add depth and texture to the story. Take your own photographs, explore the area, meet locals, and see how history is preserved and interpreted (or not) in the current landscape.

- Online groups, such as Facebook local history groups, are great sources of people willing to share memories of their hometowns from decades past. Of course, you will want to cross-reference tips received with other documents and sources to verify information.

- Census records and Ancestry databases are helpful in finding more information about key players and verifying details about their lives.

Telling the Story

Once you’ve pulled your research together, there are many ways you can share your institution’s history. Provide a written report and/or oral presentation to your staff, board, and/or community at large. Consider making a short video of your research. Timelines, biographical sketches of local activists, photo journals of current sites and landmarks, can all help tell the story. These might be shared via displays, exhibits, or programs.Partner with local organizations such as museums and historic sites that may want to share – and

contribute to- your research. Recognition is essential to honoring the achievements of the citizens-turned-activists who worked to desegregate public libraries. Their accomplishments often inspired further desegregation efforts in schools, movie theaters, restaurants, and other institutions.Researching injustices of the past leads to the question of who is still being excluded from library services today. People with disabilities, those from other language backgrounds, and people living in poverty all experience greater barriers when it comes to obtaining library services. Understanding more about past inequities and the efforts required to overcome them can help in planning for a more inclusive future.

Tags: EDISJandpubliclibraries, racialsegregationinpubliclibraries, segregationhistorypubliclibraries